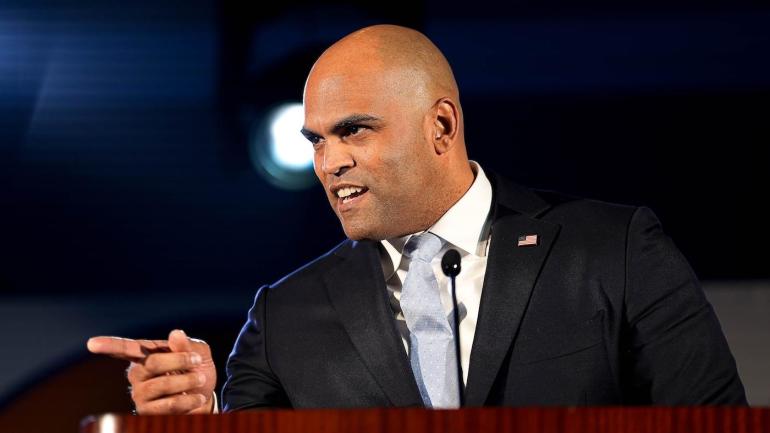

Texas congressman Colin Allred might know the ins and outs of college athlete legislation better than anyone else on Capitol Hill. From 2001-05, Allred played linebacker at Baylor University and landed in the NFL for five seasons with the Tennessee Titans. He later went to law school and served in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development before winning a congressional seat in 2018.

So much of his career success was driven by his decision to attend Baylor and set himself up for law school. But in the Wild West college landscape of name, image and likeness (NIL), would he have made the same decision? And would he have emerged as a U.S. congressman?

"I just can't imagine having to navigate this now," Allred told CBS Sports. "When I was 18, having to choose a school based on who was going to pay me the most instead of what the best fit for me would was? That would have thrown a lot of different variables into that decision."

Allred has emerged as one of the key figures in Congress pushing behind the scenes on legislation for college athletics. The House v. NCAA lawsuit settlement opens the door to direct payment from universities to athletes, but it leaves few guidelines as conferences and athletic departments wrap their heads around how to implement the most dramatic change in the history of college athletics.

Allred was raised by a single mother in Dallas and played during an era when compensation was almost exclusively limited to school and housing; his family couldn't afford to fill in many gaps. Allred would have been one of the chief financial beneficiaries as a major college football player. But while he fully supports direct payment to revenue-sport athletes, he emphasized what he sees as the bigger picture of college athletics.

"These young people are working incredibly hard, and they're producing a product that the whole world is watching," Allred said. "It's earning massive amounts of money for other folks, and they should see some of that, too. But I want to protect them because I know the vast, vast, vast majority of them are not going to play professionally."

The commonly cited stat is that only 1.6% of NCAA football players ever make it to the NFL. Allred is one of the select few who managed to beat the odds. He played 32 games in five seasons with the Tennessee Titans, joining Utah representative Burgess Owens as the only former NFL players actively in the Senate. Additionally, New Jersey senator Cory Booker played wide receiver at Stanford ("He knows that I would have taken him out," joked Allred), while Alabama senator Tommy Tuberville coached football for 40 years.

Even as a success story, Allred earned in the low seven figures across his NFL career. It was enough for a nest egg, but not enough to survive for the rest of his life. According to an analysis from CBS Sports, the market for starting power conference football talent sits in the low six figures. With five years to play four seasons, many college athletes are chasing short-term payouts that may not last very long.

"Cory and I have talked about this: I played professionally, he did not, but we both got our degrees," Allred said. "I want to see those opportunities maintained. I want to make sure that as we enter this new era with a lot of money coming in these young people -- rightfully so -- that they are still getting the most important aspect of this, which, I think, will be the opportunity to earn a college degree free of cost that will extend your earning potential far beyond your athletic potential."

His post-playing career perspective, along with being at Baylor in the 2000s, has shaped his view of college athletics. Just years earlier, track star Michael Johnson emerged from Baylor to claim the title of fastest man on Earth. Jeremy Wariner and Darold Williamson, both 400-meter runners, captured gold medals as well. Kim Mulkey built Baylor women's basketball into a winner, capturing her first national championship in 2005. Men's tennis star Benjamin Becker led the Bears to their first national championship in 2004.

None of these former athletes participated in revenue-generating sports, but many were able to elevate their on- and off-court profile with the opportunities in college athletics. Many of the opportunities also went to female athletes. Allred emphasized that any legislation will have to evaluate the role of Title IX in ensuring that high-level opportunities remain for women's athletes.

"Whether it's softball, tennis or even golf players, I think that's great that we were able to have this kind of broad range of opportunities for men and women to compete at a higher level, to get their education and potentially go and do more ... my experience at Baylor was that some of those folks that were in the non-revenue earning sports, those were incredibly important opportunities," Allred said.

When asked point blank about whether legislation to shape the future of college athletics is realistic from a divided Congress, Allred was adamant that the answer is "yes." Congressional leaders have been openly discussing various bills in support of college athletics since NIL entered the equation in 2021. At least seven pieces of legislation have been proposed, several of which were bipartisan.

Ironically, one of the top public advocates for college athletics legislation is his opponent. Allred is running to unseat Texas senator Ted Cruz in November. Cruz has proposed college athletic legislation and held several panels on the issues, including one involving former Alabama coach Nick Saban in March, which were among Saban's first public statements after retiring.

In an era when Republicans and Democrats rarely agree on anything, college athletics has quickly become a target for reform.

"I think the decks kind of cleared now in a way that I think makes it easier for us to come in and say, 'Let's have a comprehensive bill that addresses this and sets a national standard for all these things,'" Allred said. "In terms of timeframe, these things can come together quite quickly. I wouldn't say that it's impossible for it to happen this year, although everyone who knows anything about Congress knows that in an election year, it's harder to do things.

"I am hoping that we can do it as soon as possible," he continued, "but I think that certainly in the next year or so you'll see serious legislative efforts around this."