OAKLAND, California -- Over pancakes and Eggs Benedict at the Cock-A-Doodle Café, a quaint, downtown breakfast spot, Billy Hunter peers through the window onto sun-splashed Washington Street. He's contemplating a question that cuts to the core of his downfall as the former executive director of the National Basketball Players Association.

What do you want to tell people about you that they don't know?

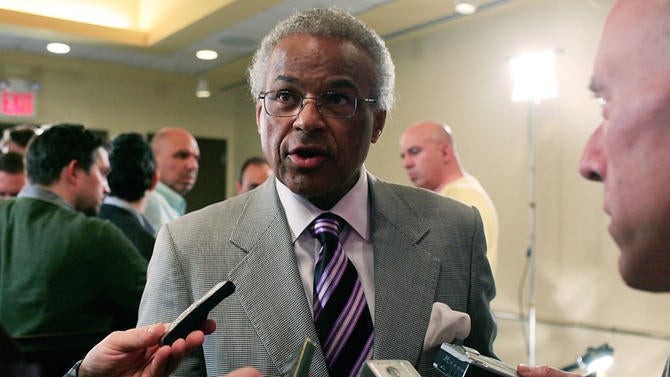

Still quick on his feet and 35 pounds lighter than the day he was fired three years ago from the only job he'd known for 17 years, Hunter suddenly goes silent. He pauses for 10 seconds, then 20. Soon it's an NBA shot-clock violation; then, a college violation.

Voices rise and fall and silverware clings and clangs in the small restaurant in Hunter's old stomping ground -- downtown Oakland, where he was once a swashbuckling federal prosecutor, and later, a high-profile defense attorney. Fifty-three seconds later, he delivers the answer.

"Just that I always acted in the best interests of the players," Hunter told CBS Sports in his first interview since he was removed from his post under a cloud of suspicion. "I always put their interests first."

Hunter seems smaller, and his voice is softer now, though somehow he's no less bombastic. He's always been a fighter; an underdog in the perpetual tug-of-war with billionaire owners and the NBA's army of lawyers. As the league prepares for a monumental and chaotic free-agency period that begins Friday at 12:01 a.m. ET, Hunter feels at once vindicated and victimized.

Vindicated, because the players he was accused of selling down the river in the 2011 collective bargaining agreement are doing surprisingly well six years later. Though their share of league revenue was drastically reduced, an unprecedented boom in business has sent total salaries skyrocketing. League revenues have grown by nearly $1 billion in the last three years. Since the lockout, the salary cap has exploded by 162 percent.

When the league's nine-year, $24 billion TV deal begins hitting the system with the dawn of the new league year on Friday, a period of unprecedented spending will commence. By next summer, LeBron James will shatter Michael Jordan's league record annual salary of $33.1 million in what will be the first $200 million player contract in NBA history.

"That's why the owners are crying," Hunter said. "... Ironically, some agents have called me now who wanted my head before and they thanked me for the deal. They said it's been very lucrative for the players."

Victimized, because Hunter, 73, believes he was unfairly ousted in a one-sided inquisition that didn't allow for him or anyone on his behalf to respond to the allegations that he put his personal interests ahead of the players' and failed to properly manage conflicts of interest.

"It was overnight," Hunter said. "The next thing I knew, I was gone."

The NBPA's executive committee unanimously ousted Hunter in February 2013 on the heels of a blistering report from famed sports attorney Ted Wells alleging wide-ranging shenanigans. Hunter sued the union alleging breach of contract; the NBPA filed counterclaims in 2015. Each side has been forced to retrench at times and has been able to claim small legal victories along the way. A recent ruling from Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Huey Cotton favored Hunter when 12 of the union's 14 counterclaims were thrown out.

The union then filed an amended complaint narrowing its action to seven claims and removing the Wells report from the filing. The case now gets down to the potentially explosive phase of discovery. In a subsequent ruling May 16, Cotton ordered the NBPA to produce documents related to the preparation of the Wells report before deposing Hunter. NBPA lawyers continue to resist turning over the work product behind the report that doomed Hunter's tenure and have filed a motion asking Cotton to reconsider his ruling, a person familiar with the proceedings told CBS Sports.

"There was nothing to rebut what Ted Wells and others were saying behind closed doors," Hunter said of the 2013 meeting in Houston where he was ousted in absentia. "I think it was pretty one sided."

Hunter, who sat for the interview with one of his attorneys, Joshua Hill, is seeking at least $10.5 million in salary and severance he claims he is entitled to under a 2010 contract extension that was executed by then-NBPA president Derek Fisher, who later turned against him. (Defamation and other claims against Fisher and his business manager, Jamie Wior, are no longer part of the case.) The union claims that the contract extension was not valid because it had not been properly ratified by the Board of Player Representatives.

"The NBPA has delayed Mr. Hunter's day in court for more than three years, but the NBPA cannot delay forever," Hunter's lead attorney, David Anderson, said in a statement to CBS Sports. "The NBPA promised Mr. Hunter a guaranteed severance payment in a contract signed by Derek Fisher as the president of the union in 2010. Mr. Hunter earned that guaranteed severance payment when he negotiated the most lucrative collective bargaining agreement in the history of the NBA in 2011."

In a statement, the NBPA said: "We are pleased that the judge ruled that the NBPA's primary claims against Mr. Hunter for breach of fiduciary duty will go forward. Those claims encompass all of the misconduct for which the NBPA seeks to hold Mr. Hunter accountable."

In the meantime, Hunter has transitioned into a simpler lifestyle as a grandfather, Little League coach and chauffeur for his four grandchildren, ages 5 through 9. He and his wife, Janice, split time between Harlem and their residence in the Crocker Highlands section of Oakland.

He's traded in his former life of bare-knuckle negotiations with the commissioner's office for shuttling his two youngest grandchildren to karate practice and Kumon. He drives them to and from school every day, too, in his soccer-mom mobile -- a Chevy Suburban.

"I do a lot of hugging and kissing, which I never did before, with these grands," Hunter said. "I'm forever hugging them and kissing them, telling them how much I love them, how much they mean to me, how my life would be empty without them. Obviously, you're concerned at this stage in life how much time you have left. I'm going to be 74 my next birthday. My whole idea, my whole effort is to make as much impact on them as I can."

The years of stress took a toll on Hunter's health. Since his ouster, he's been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and had six stents implanted in his arteries.

"You can't get any more than six," Hunter said. "I'm maxed out."

His wife implores him to address the disease with nutrition and exercise, so he can get off the steady diet of pills he has to down twice a day. The pancakes and syrup on his plate on this morning during the NBA Finals, he said, are a rarity.

He misses the job, but on the other hand, the ongoing collective bargaining negotiations with commissioner Adam Silver are no longer his problem. His replacement, Michelle Roberts, is engaged with the league in an effort to recalibrate the agreement to reflect the league's post-lockout largesse. The goal is to reach a new agreement before either side can opt out of the 10-year deal on Dec. 15.

The biggest issue is the massive increase in TV revenue, which threatens to disrupt the system changes that the league insisted on six years ago to restore competitive balance. With the salary cap rising from $70 to $94 million -- and the tax from $85 million to $113 million -- contending teams are getting a rare chance to get even better and big spenders are receiving a get-out-of-jail-free card.

The dynamics have changed so much, so quickly that Silver -- in his pre-Finals address -- significantly walked back his rhetoric on competitive balance. He changed the terminology to "equality of opportunity," and admitted, "We're never going to have NFL-style parity in this league."

Silver, the NBA's lead negotiator during the lockout as deputy commissioner under David Stern, has said the spike was unavoidable because the dramatic increase in TV revenue couldn't have been anticipated. Hunter disagrees.

"The one thing that I do remember saying to the players was that we had to be conscious of the fact that the revenues were going to jump significantly because of the TV money," Hunter said. "And I'd said that I knew that it would at least double; I didn't expect it to triple, but I knew that it would at least double. ... It's not credible for the NBA to make that claim."

The league office had no comment on Hunter's assertion. But while the league office also thought at the time it was plausible for broadcast rights fees to double, neither side expected them to triple -- an outcome that is about to flood the system with about $1 billion in salary cap room. Hunter's successor, Roberts, rejected the league's proposal to smooth the additional money into the player compensation pool.

For the third straight year, the league will have to write a huge check to the union to cover a shortfall between the players' negotiated 50 percent split of basketball-related income (BRI) and the actual revenue. By the end of next season, Silver has projected that the shortfall could balloon to $500 million.

"The kicker I put in there," Hunter said, "was that they had to spend up to 90 percent of the cap. That's why it's a killer."

All of his observations are from afar now. Hunter has not attended a single NBA game since his ouster.

"Why not?" I asked.

"I guess because I'm embarrassed, putting it bluntly," he said. "I'm embarrassed. I left under a cloud."

He also left behind years of knockdown fights with his nemesis, Stern, with whom he has not crossed paths since he was fired. Given their contentious relationship, don't hold your breath.

"David and I had a peculiar relationship," Hunter said. "I don't know that we were always distrusting of one another. I respect David for the job he did. I think he did a great job and the league is the beneficiary. I don't think I ever got any credit, even from the media. You guys were the ones who made all the characterizations and I was always scratching for whatever I could get.

"I don't dislike him," Hunter said. "The difference was, I had a job to do and he had a job to do. And I did it. I didn't let anything interfere with that."